A Guide to Gamle Bergen

- 0 comments

- by Emma

A Guide to Gamle Bergen

For me, Gamle Bergen was one of those places I occasionally took groups, but never really understood. I never had the chance to go there myself, and when I was with tourists I was too busy with them. As a tour guide, I memorised information about the important houses, and always made sure to give them their maps and point them in the right direction, but that’s about it. I never understood why to make the journey to Gamle Bergen when modern Bergen is full of old houses!

With the corona situation, I’ve had much more free time to go exploring, and it’s finally giving me the chance to build up this blog. I decided that I would visit Gamle Bergen and write about it for Hidden North, hoping to find some new appreciation for the museum. And boy, did I!

So, for my Gamle Bergen Guide, I’m going to go over what you can see at the museum but also the hidden attractions around the museum because, honestly, they are just as special (and they are free!)

In this article...

What is Gamle Bergen?

Gamle Bergen (English: Old Bergen) is an open-air museum located a few kilometres outside the city centre of Bergen. The museum was established to save the characteristic houses that represent Bergen architecture. Bergen did catch fire often!

The museum’s founder was Kristian Bjerknes (1901-1984), a cultural historian and member of a group of likeminded locals. He became the first director of the museum and ran it until 1971. As the city was expanding at the beginning of the 20th century, the widening of streets led to the demolition of many of Bergen’s wooden homes. The museum group would instead take the houses and place them on their site.

In 1944, a German freight ship exploded on the Bergen Harbour. The explosion damaged many wooden houses, and the museum sped up its efforts to save these buildings. They were rebuilt at Gamle Bergen.

The museum has 32 houses plus smaller buildings and items from the old times. Gamle Bergen’s purpose is to highlight Bergen’s history and cultural life, with objects and information boards telling about what it was like to live in Bergen in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Historic Overview of the Site

Gamle Bergen was built on Elsesro, an old summer estate. The wealthy shipbuilder Rasmus Rolfsen had Elsesro built to accompany his boatyard. He named the site Elsesro after his wife Elsebe (Elsesro = Else’s Peace). In the 19th century, the pavilion, gatekeepers house, summer house, tower house and barn were added.

Rasmus Rolfsen’s son, Tønnes Rolfsen, expanded the main building when he moved in. Damsgård Manor, which sits directly across the fjord, likely inspired the architecture of the building. Tønnes Rolfsen also had Haugen built, with its Chinese pavilion, park and ponds, designed in an English garden style.

After Tønnes Rolfsen passed, his son Rasmus Rolfsen took over the property and continued using it as a shipbuilding business. The shipyard operations were ceased and the business was abandoned in 1839. Rasmus Rolfsen, on his travels to Copenhagen, had become interested in the liquor business and decided to use the property for that. The business didn’t last long; in the second half of the 19th century, the property was a paint-making business.

When Rasmus Rolfsen died in 1903, he left no descendants. The city took over the estate in 1906. From 1911 to 1916, the property was used as an orphanage for children from tuberculosis homes. From 1919, the building was used as a nursing home for children with syphilis. The purpose of sending the children there was to isolate them to prevent infection as well as sure them. This home was abandoned in 1939.

From 1936, the Gamle Bergen Association took over Elsesro in several stages, and in 1949 the museum opened with the first restored houses.

I’ll go over the original buildings a little more on the walk-through.

On the way to Gamle Bergen

For my guide below, I walked from Bryggen to Gamle Bergen. Therefore, my walk starts on the opposite side of the park from the main entrance. Honestly, I found it a lot nicer than using the main entrance, which is on a dirt road. It’s much more peaceful using the side entrance as you pass these lovely historic homes as well as the old shipyards.

The Ropemakers House

The point in which you leave the main road to walk to the Gamle Bergen entrance begins at the recently restored Ropemaker’s House. This lovely 19th century home was the residence of the owners of the ropeworks you’ll see behind it.

The area you walk through now is an area that has many historical monuments. Sadly it’s also an industrial area, so there’s a mix of history and then ugly modernity.

Måseskjaeret

Hidden amongst the industrial buildings is Måseskjaeret, a 1798 villa (lystgård in Norwegian) that sits out on the water. The building has been converted into modern warehouse buildings.

Ditleffsengen & the Sailors Homes (Strandens grend)

Ditleffsengen is another 18th-century villa we pass on our left.

After this building, we pass a village-like cluster of old houses known as Strandens grend today. These were the homes of sailors as well as workers at the factories. They also signify the northernmost part of Sandviken.

Holmefjordboden

This building was built in 1804 for merchant Johan Ernst Mowinckel, who imported corn, textiles and other ‘kolonial’ products. For a while, this was also a stockfish warehouse.

Masteboden

Masteboden, or the ‘mast booth’ is part of the original Elsesro property; and is the long brick warehouse on the waterfront. It was the building that was built to repair the Russian ship. Rasmus Rolfsen repaired the ship, a task which took one year and 8 months. The building is probably the largest privately owned Empire-style brick building in Bergen.

The Old Postal Road

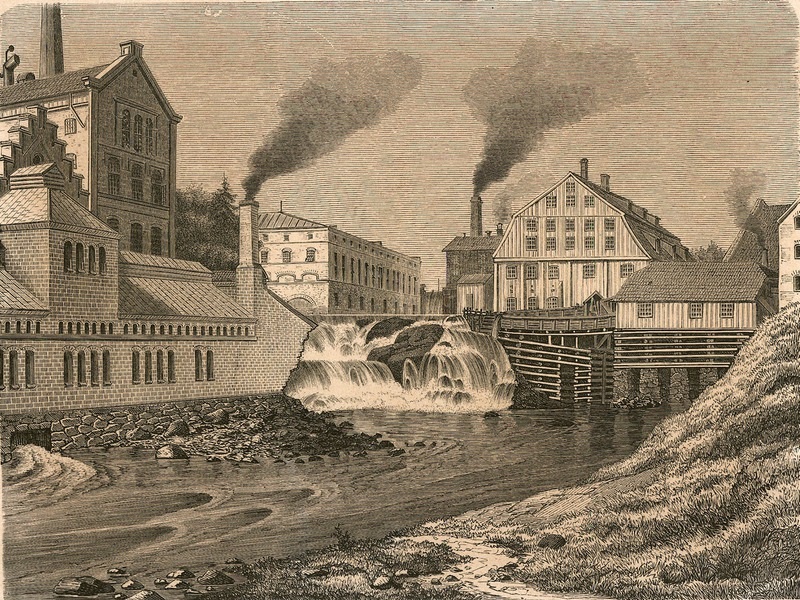

Just before the Gamle Bergen entrance, close to the gate there is the first leg of the postal road that ran from Bergen to Trondheim; the route can be followed for many kilometres into the hills above the modern street of Helleveien. At the side of it is a water mill which incorporates the vestiges of one fo the largest mill complexes of Old Bergen, Storemøllen, which began in the 16th century. It was torn down in 1971.

Gunhilds River

The brook, besides being a remnant of a once so forceful stream that propelled the giant wheels of the mill, is a historic landmark of the first rank. This is Gunhildåen, ‘Gunhild’s River’, which is mentioned in Bergen’s City Laws of 1276 as being the northern boundary of the city; from here the boundary ran inland far into the hills before turning southward.

Today the river is called Sandvikselven (Sandvik River), and it comes out of a ravine called Munkebotn (The Monk’s Hollow). The name derives from the fact that in the Late Middle Ages the Dominican brethren in Bergen had property and mill rights in this area.

Inside Gamle Bergen - the free part

Now it’s time to go into Gamle Bergen. As we do, it’s worth noting that the park can almost be seen in two parts: there is a free part you can walk through (it’s very popular with locals) and see most of the buildings from there.

There is also a paid portion of the park, and that consists of the famous ‘street’ and surrounds. During the summer months, the buildings in the paid portion of the park are opened up and you can step inside and view exhibitions. Additionally, they have actors representing people from the 18th and 19th centuries that you can talk to, and they give little demonstrations throughout the day.

The paid portion of the park is only for the summer months, May to September, and outside of those months you can explore the paid portion of the park for free, however the buildings are closed up.

Does that make sense? I think so. Let me summarise:

- Free Park: Some buildings. Open all year

- Paid Park: Best preserved buildings. Costs money between May-September with entrance into the buildings and exhibitions. Free off-season, but the buildings are closed.

Now let’s do the free part of the park first.

Elsero

One of the first buildings you’ll pass is Elsesro, the original summer residence. The central part was built by shipbuilder Rasmus Rolfsen in 1785, while his son Tønnes Rolfsen added the two wings around 1810 to make it look more grant. Tønnes made the property into a miniature manor that was very popular at the time; he had the whole area landscaped and created dams and small waterfalls.

Today Elsesro is a lovely Norwegian restaurant.

The Park

If you continue past Elsesro, you’ll soon arrive at the garden, which has been designed in the style of an English garden. This was a common type of park in the 18th century. To speak romantically, the English garden was to emphasise man’s rational and emotional sides. At the same time, the park was supposed to look natural.

Today it’s the home of some ducks and geese.

The Pavilion

The pavilion was part of Tønnes Rolfsen’s expansion, and it was designed in a Chinese style. The view from the pavilion once inspired J.C. Dahl to paint one of the finest views of the hometown, but Edvard Grieg also found inspiration here. He borrowed the pavilion in 1873/74 to serve as his studio while writing the music for Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s play Olav Tryggvason and then for Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt.

While the pavilion is nice, it’s the view you come here for. You can see three of Bergen’s seven mountains, Sandviken, and the city fjord. On a sunny day, this view is everything. It’s easy to see why artists like J.C Dahl and Edvard Grieg would come here for inspiration of their city.

If you walk along the park, you’ll see a lovely white manor hiding behind the trees.

Frydenlund

Frydenlund was built in 1797 for the wealthy merchant Lorentz Holtermann as his summer estate at Sandviken. The name means ‘grove of delight’ and became a major summer estate for himself and his family.

The house consisted of Lorentz, his wife Anna Margrethe, their five small children, a housekeeper, four serving girls, a farmhand and three merchants clerks. Holtmann sold the property in 1832 and it was passed around by various wealthy merchants. In 1870 it underwent a major renovation. After the war, it had to be demolished to make way for a housing project, so it was moved to Gamle Bergen in 1949.

Inside Gamle Bergen - the paid part

Now let’s move on to the paid portion of the park. As mentioned above, you can go inside the buildings and see exhibitions there. I’ll try and get back later this year to take photos of the interiors, but for now, I’ll explain each building you can see.

Let’s start with the so-called ‘main street’. I’ll go through the buildings in order as if you were walking up the hill and passing them.

The Watchmaker's House & Sea Captain's House

The watchmaker’s house (green) and the sea captain’s house (white) are located at the bottom of the hill.

The Baker's House (The Yellow Building)

The Baker’s House was built in 1728 to house, you guessed it, a bakery. Originally the building was one floor; the second storey and attic were added in 1788.

This wasn’t just any baker’s house; this was the home and bakery of Master baker Ditlef Martens. His son, Nikolai Martens, ran the bakery from 1840 and the Martins family owned 11 bakeries in the city. Back then, the profession of the baker was a privileged status, and there could only be 25 bakers in the city.

Nikolai Marten’s great grandfather, grandfather, father, brother, son, grandson and great-grandson were all master bakers in Bergen. This particular bakery was located just behind St. Mary’s Church. The bakery operated until the 1944 explosion.

The Merchant's House (The Blue Building)

The Merchant’s House is an example of a Norwegian merchant’s home in Nordnes; this building was located just behind Nykirken Church. Originally this building would’ve had a lovely courtyard, stone cellar, and washhouse. As Bergen became increasingly populated in the 19th century, this house was converted into a three-storey apartment building. In total, there were six apartments.

Once at the top of the hill, you’ve reached the main square. I’ll go around the buildings clockwise from here.

The House of Craft and Trade

The home dates back to after the fire of 1756. It functioned as a residence until it moved to Gamle Bergen. It houses various artisan workshops, though it was originally a residence.

Inside the building, you can see a printing press, bookbinding workshop, Bergens Tidende (Newspaper) office, plumber workshop, and photo studios with waiting rooms.

The Glazier's House

The home dates back to after the fire of 1756. It functioned as a residence until it moved to Gamle Bergen. It houses various artisan workshops, though it was originally a residence.

Inside the building, you can see a printing press, bookbinding workshop, Bergens Tidende (Newspaper) office, plumber workshop, and photo studios with waiting rooms.

The Town Hall

This building was originally owned by the Solhimsviken Indremisjonsforening (Solheimsviken Evangelical Association), which used the hall as a chapel. Yes, this is a religious building! Doesn’t look like it today, right?

When Solheimsviken was undergoing a major renovation in the 1970s, the chapel was expropriated, and then in 1977 Gamle Bergen was offered the building. The museum uses the hall for assembly events, so all the religious symbols have been removed.

The House of the Official

You can tell this was the house of the official. Back then, the most privileged houses were completely symmetrical; compare this to the merchant’s house, the baker’s, or the glazier’s house, for example.

The House of the Official stood on Kong Oscars Gate (near the Leprosy Hospital/City Gate (Stadsporten). Carsten Lydkien, a customs agent and police prosecutor, lived here from 1795. The property remained a single-family home until 1914, something not many houses in Bergen can claim.

Dentist's House

This is another Nordnes building; in fact, it was the neighbour of the merchant’s house. It was a residence for a middle-class family. The building itself underwent a modernisation in the 19th century, getting a lovely new Swiss-style facade. The building is converted into a dentist’s home and surgery representing the period 1885-1900. Take a look at the dentist’s equipment if you can go inside. Thank god we live in the 21st century.

There is also an umbrella business in the building, because Bergen.

Dorothe Engelbretsdatters House

Dorothe Engelbretsdatter is a well known Bergen priest and writer from the 18th century. She is the first known female writer in Norway.

Dorothe lost her original home in the 1702 fire. As a priest, she had trouble building a new house and lived for a long time in a poor house. When King Frederik IV of Denmark/Norway visited in 1704, Dorothe handed him a poem and prayer letter and asked for his help for a new house. He didn’t help her. After she asked the city authorities in 1709 she got her house.

The Grocer's Shop

In Norway, grocer’s shops were referred to as ‘Kolonial Stores’ because they were where people would buy goods ‘from the colonies’. These shops started appearing in the 1870s, but it was not until the 20th century that this type of shop began to dominate the grocery trade. Back when the Kolonial Stores were the grocery shops, they were special local shops. Goods weren’t stored in people’s homes like they are today. Grocery products were bought in small quantities every day. It’s kind of like a ‘storeroom’ for the nearby houses.

Krohnstedet

Krohnstedet is a typical summer estate that appeared in Bergen in the 18th century. It was built for the wealthy merchant Hans Krohn. Hans Krohn ran one of the city’s biggest shipping companies that imported and sold wine. He had twelve children with four wives, and only six children survived to adulthood.

The house is accompanied with by caretaker’s house, which was common at the time.

Now make your way back to the main square. Once at the main square. You’ll see there is a path that runs in front of the sailor’s house. It’s a lovely secret path where you can see the backs of these old buildings. It will also take you back to where we began and marks the end of my little walk!

Now onto the practical information.

Practical Information

Opening Hours

Gamle Bergen is open from mid-May to mid-August.

During mid-August to mid-May, you can still walk around Gamle Bergen for free. Just keep in mind that you can’t go inside the buildings.

Getting There

Walking

Gamle Bergen is a thirty-minute walk from Bryggen. The walk is mostly flat, with some gentle inclines. It’s a lovely walk; you walk through historic Sandviken before turning off to reach the ropemaker’s house. For my above walking tour, I walked from Bryggen and took the back entrance from there.

Bus

From Bryggen:

Take Bus 3, 4, 5, 6 from the bus stop in front of the wooden houses. The bus ride takes 10 minutes and the name of the bus stop is ‘Gamle Bergen’. Once off the bus, cross the road and follow signs to Gamle Bergen. This takes you to the main entrance, not my side entrance.

Tickets can be bought via the Skyss App, on the bus (for 2x the cost of the app), or at a ticket machine.

I hope you liked my Gamle Bergen guide 🙂

Sources:

Gamle Bergen brochure

Nordhagen. Per Jonas. Bergen Guide & Handbook. Bergensiana-Forlaget. 1992.