The History of Longyearbyen

- 0 comments

- by Emma

The History of Longyearbyen

If you’re going to Svalbard, you will be going to Longyearbyen. The only settlement open to the public to stay at, Longyearbyen is the hub of Svalbard and starting point for all the expeditions and day trips around the archipelago.

While today Longyearbyen as a vibrant, modern and lively town centre, this is all very recent. For the first several decades of the towns existence, Longyearbyen was a harsh and inhospitable place cut off from the rest of Norway. However, people chose to come here because of the mining activity that has been taking place here since the towns inception.

Before you to go Longyearbyen, be sure to understand a little of the settlements history. Here is my History of Longyearbyen.

In this article...

Be sure to read my detailed travel guide for Svalbard, including all the settlements and itineraries for different times of the year.

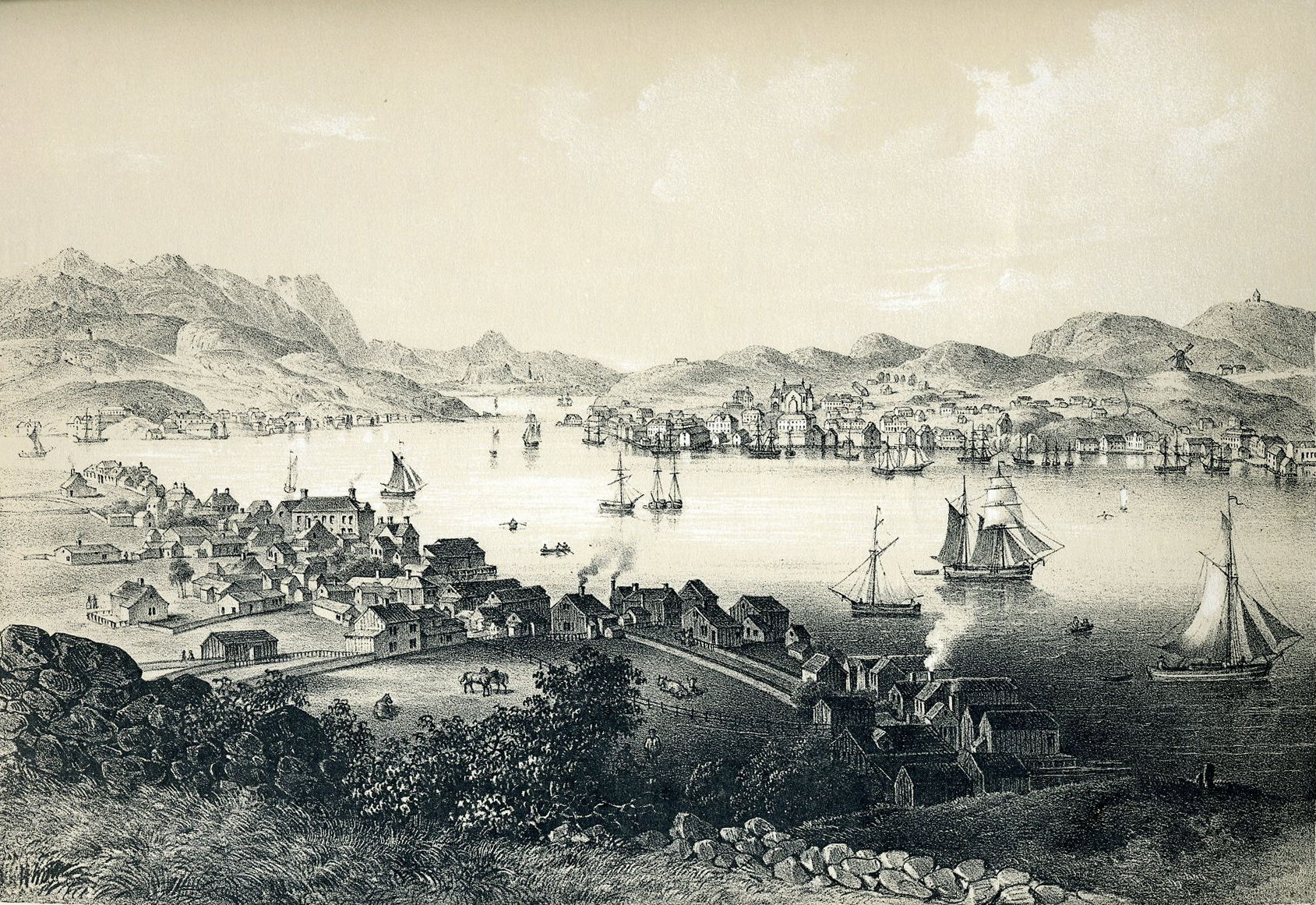

Early years of Longyearbyen

Longyearbyen, nestled in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, boasts a captivating history woven with exploration, mining, and Arctic survival. While it was a place where there were hunters and explorers from the 17th century onwards, many consider Longyearbyen’s beginnings to be mining, but that’s not totally true. In fact, the first reason for people coming to Longyearbyen was tourism. In 1896, Vesteraalens Dampskibsselskab (later Hurtigruten) started tours to Hotelneset, the name of the peninsula where the airport is today. A prefabricated hotel was built and two families lived on the property all year round. A post office operated by the Norwegian Postal Service was even established here. However, this wasn’t a successful business because of the cost of maintaining the property.

John Longyear & the Discovery of Mining

The American industrialist John Munro Longyear visited Spitsbergen in 1901 as a tourist and met an expedition prospecting for coal. Two years later he came back and got more information on the coal fields. Longyear bought the Norwegian claims on the west side of the Adventfjord, and in 1906 started the Arctic Coal Company. Mine 1a was the first mine to operate at Longyearbyen. The company had American administration but mostly Norwegian labourers and they built accommodation and docks for the workers. The name of the settlement – Longyear City. The aerial tramway that is still visible on the mountainside was used to transport the coal from the mine to the port. Mine 2a opened in 1913.

The American-owned company did not last too long. Financial difficulties during World War I led to the mining operations being bought by the Norwegian company Store Norske, which was incorporated in Oslo in 1916. Store Norske built five new barracks and a hospital. Store Norske owned a great deal of the town. Store Norske even had their own money (with approval from Norges Bank), consisting entirely of banknotes at par with the Norwegian krone.

Mine 1 closed in 1920 after 26 men were killed in a coal dust explosion. Remains of the mine are still visible on the mountainside.

Establishing Longyearbyen as a Town

As mentioned above, a hospital and even money were brought to Longyearbyen in the 1910s. In 1920, the Church of Norway appointed Svalbard’s first vicar and teacher – Thorleif Østenstad. A school was established jointly by the church and Store Norske. At first, there were 8 students here. The first church in Svalbard opened in 1921, though was eventually destroyed during World War II.

Because Store Norske now owned mining activities, the town was renamed Longyearbyen in 1926.

Tourism began in 1935, when SS Lyngen started calling regularly during the summer season. In 1938, Longyearbyen’s first road was completed and linked the town with Sverdrupbyen further down the valley.

World War II

During World War II, Longyearbyen gained strategic significance due to its coal resources and suffered bombings by German forces in 1943. Initially Longyearbyen was unaffected by the war, but soon it became clear that Svalbard was of strategic important. On 3 September 1941 the population (765 people) were evacuated from Longyearbyen to Scotland. A small Nazi garrison and air strip was established in Adventdalen, mostly to provide meterological data. After the British Operation Ftirham regained control of Barentsburg, the Nazis left Longyearbyen without combat.

In September 1943, the Kriegsmarine dispatched two battleships, Tirpitz and Scharnhorst, and nine destroyers to bombard Longyearbyen, Barentsburg and Grumant. Only four buildings in Longyearbyen survived – the hospital, power station, office building and a residential building. The first ship leaving the mainland to repopulate Longyearbyen left on 27 June 1945.

Immediate Post-War Development

Post-war, the Norwegian government took control of mining operations, leading to further development and stability. By 1948, coal production had reached the pre-war level. The neighbourhood of Nybyen was established in 1946 and consisted of five barracks, each housing 72 people.

The first issue of the Svalbardposten newspaper was published in November 1948. A year later, Longyearbyen got a telephone connection to the mainland. The cemetery that had been established in the 1920s closed in 1950 because the bodies were not decomposing due to the permafrost and keeping them risked disease. Since then, bodies have been sent to the mainland for burial. The community centre Huset opened in 1951.

'Normalising' Longyearbyen

In the 1960s, the town began its modernisation process. The first snowmobile was brought here in 1961, and by 1969 there were 140 registered snowmobiles against 33 registered cars. Television broadcasting equipment was installed in 1969, with the schedule of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation being aired with a two-week delay. Television became live in 1984.

In 1971, a new school building opened along with a gymnasium and swimming pool. In 1978, an upper secondary program was introduced at the public school.

The Svalbard Council was established on the 1st of November 1971 and it consisted of three different groups: Store Norske employees, government employees and others.

The airport opened in 1975 and initially provided four weekly services to mainland Norway and semi-weekly services to Russia.

Do you remember the Store Norske money that was introduced back in the early days? That was taken out of circulation in 1980 and the Norwegian kroner has been used since then.

Svalbard Samfunnsdrift, a company responsible for public infrastructure and services, was established by Store Norske in 1989. They are responsible for healthcare, the fire brigade, the kindergarten, roads, rubbish disposal, power production, the water and sewer system, cinema, cultural activities, and the library. Ownership was taken over by the Ministry of Trade and Industry in 1993.

Modernisation of Mining

Mines continued to open around Longyearbyen in the 1970s. Mine 3 opened in March 1971, and Mine 7 opened in 1972. In 1973, the Ministry of Trade and Industry bought a third of Store Norske – eventually it owned 99.94% of the company.

From 1982, Store Norske permitted private individuals to own and operate cars, and by 1990 there were 353 registered cars and 883 snowmobiles. Store Norske moved their headquarters from Bergen to Longyearbyen in 1983.

Modern Times

Over time, Longyearbyen modernised, improving infrastructure and amenities for its residents. This process has been called ‘normalisation’ and included introducing a full range of services, a varied economy, and a local democracy.

Yet, economic challenges emerged in the latter half of the 20th century as coal prices declined, prompting a shift towards diversification. Mining is planning on closing in Longyearbyen altogether. The first major hotel opened in 1995 (now the Radisson Blu), the Longyearbyen Community Council was established in 2002, and the University Centre in Svalbard opened on 6 September 1993 and had 30 students. Telenor mobile was introduced in 1995, and in 2004 the Svalbard Undersea Cable System opened, providing fiber-optic cable connection to the mainland. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault opened in 2008.

Today, Longyearbyen’s economy revolves around tourism, research, and education. As a base for scientific expeditions, Longyearbyen hosts research institutions studying climate change, wildlife, and geology. However, it also faces unique challenges, such as extreme Arctic conditions and the impacts of climate change. Despite these obstacles, the town has adapted, implementing measures to ensure safety and sustainability.

Longyearbyen’s cultural heritage is preserved through museums, historic sites, and local traditions, celebrating its diverse influences from Norwegian, Russian, and American backgrounds. Ultimately, Longyearbyen’s history embodies human resilience and exploration in one of the world’s most unforgiving environments.

Be sure to read my detailed travel guide for Svalbard, including all the settlements and itineraries for different times of the year.