Exploring Oslo’s Old City Christiania: Self-Guided Walking Tour

- 1 Comment

- by Emma

Self-Guided Walk: Christiania in Oslo

Christiania was the name of Oslo between 1624 and 1925. The name came from King Christian IV, who made the big decision after a fire in 1622 to move the whole city from its original location to be close to the Akershus Fortress. He laid the city out in a grid pattern (the area is called Kvadraturen, which refers to the grid layout), and designated certain blocks for certain purposes. And so, Christiania was built.

Many of the original buildings are now gone, but some still stand, albeit many are heavily renovated. Still, Christiania is a fascinating place to walk through and learn about how the old city of Oslo functioned.

On this self-guided walk, I’ll show you the buildings still standing, the story behind them, and try to give you an idea of what Christiania used to be.

A Brief History of Christiania

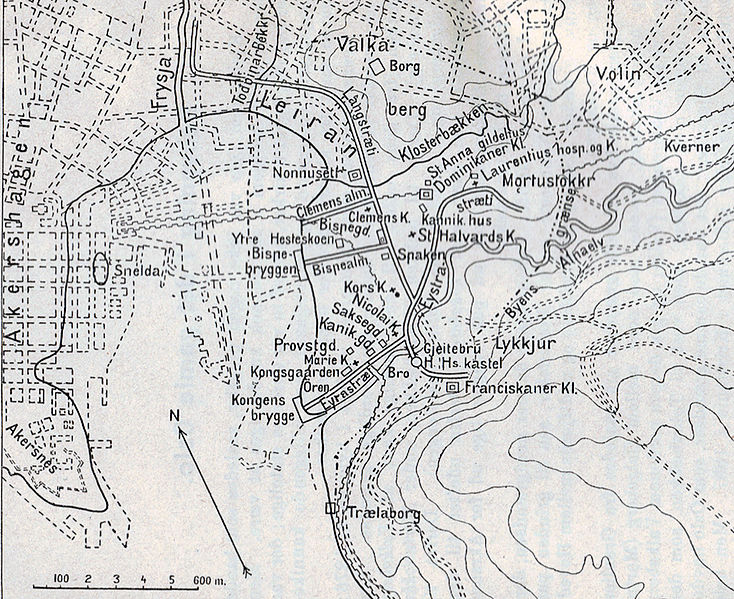

Christiania was established as a replacement of the old city of Oslo in 1624, after a huge fire had swept through the original city. Oslo stood a few kilometres to the east, but King Christian IV wanted the city to be closer to the Akershus Fortress. The ruins of the old city still stand at the suburb called ‘Gamle Oslo’.

The streets were built very wide, and the city was surrounded by ramparts to better protect itself. Additionally, all the houses were to be built in brick as a modern fire measure. However, most people were still too poor to build in brick, so wooden houses or half timber houses were constructed. The plots of land within Christiania were distributed to the citizens free of charge, but were allocated according to wealth and status.

The walled city of Christiania didn’t last long: after a fire in the 1680s the ramparts were no longer used and the city began to see unregulated expansion outside the walls. The city’s population rose steeply after the union with Denmark ended, and more modern buildings were built in Christiania to show off the city as a capital, including the palace, parliament and university.

By the early 20th century, the area of the original Christiania was a quiet business activity and no longer the centre of the city. In 1925, the city got its original name of Oslo back. Today, Christiania is distinctive on all maps of Oslo thanks to its grid pattern. It’s known as ‘Kvadraturen’ on maps, which refers to the grid pattern.

In this article...

Downloadable Version of This Guide

We offer downloadable versions of our self-guided walks on our online store.

Online Guide

- Information about points of interest

- Images of each point of interest

- Historic overview of the neighbourhood

- Directions between points

- Historic photos

- Information about facilities along the way

Downloadable Guide

- Information about points of interest

- Images of each point of interest

- Historic overview of the region & towns

- Directions between points

- Historic photos

- Facilities including supermarkets, toilets, petrol, hotels, cafes, restaurants with addresses.

The online guide is a summarised version of the downloadable guide. Some points of interest are only included in the downloadable guide.

Christiania Self-Guided Walk

Christiania Torv

This is the centre of the old town of Christiania. When Christiania was completed, the Holy Trinity Church stood on this site. It was the first public building to be completed in the old town, and by it would’ve been the market. The market was used on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and farmers would gather to sell their goods. The annual winter market in the first few days of February was also held here. Farmers came from all over Eastern Norway with butter, hides and venison. In the square was also the gauntlet and a ‘kag’ – a cane with a neck iron. Here the criminals were whipped and shamed.

The Holy Trinity Church used to stand here. It was a Renaissance building with four clocks and a richly decorated interior. Sadly, the church wasn’t even completed before it was struck by lightning in 1686. The bells of the church melted, and the nave was ignited. The fire destroyed about a third of Christiania, the northernmost part – which was the poorest area and mostly wooden houses – being the worst affected.

The church wasn’t destroyed during the fire, but it was decided to tear it down anyway because Akershus Fortress wanted an open field in the area and the church was blocking the firing range of the fortress. The Holy Trinity Church was demolished, and the site was left unused. What survived of the church was moved to the Oslo Cathedral when it was completed.

Christian IV's Glove

The statue in the middle of the square is called Christian IV’s glove and is by Wenche Gulbransen. It’s supposed to represent Christian’s decision to move the city here.

Anatomigården

This is one of the few remaining half-timbered houses in Christiania. The exact age of the property is unknown, but it is believed to be from the early 1700s. The name Anatomigården refers to the fact that the Faculty of Medicine had its anatomical hall here.

Rådmannsgården

This is one of the oldest buildings in Oslo and the best-preserved building in Christiania. It was likely built around 1626 in a Dutch/Danish Renaissance style. It used to be much larger but has undergone many changes over the years. The building was built for councillor (rådmann in Norwegian) Lauritz Hansen. Today there is a restaurant inside.

Gamle Rådhus

This is Christiania’s first town hall (Rådhus in Norwegian). The building dates to 1641, though it has undergone many changes over the years. For example, it used to have a tower, but it was torn down in the 1700s. The original Renaissance gables are also gone.

In Christiania, the town hall functioned as both a meeting place for councillors but also a gathering place for the towns bourgeoise. Kristiania was ruled by two mayors and 12 councillors appointed by the sheriff of Akershus Fortress. In the cellars were a detention room and a prison for convicted criminals.

The building was in bad condition throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and over those years it was a Masonic Lodge. In 1983, it became a restaurant called “Det Gamle Raadhus”.

Revierstredet

The name comes from Revieret, a canal that was excavated in the area in the 17th century.

The dark brown building that you’ll follow along Revierstredet and then later onto Kongens gate is the oldest building you’ll see on this street. It was built in 1638 for a town bailiff and eventually became an orphanage. While it was an orphanage, 50 kids would be here. The women had to do yarn spinning, while the boys did carpentry. On the side, you can see the initials MHS and UMB, who were for the original owner’s Mads Haraldssøn and Annichen Mecklenburg. Parts of the property are among the first to be built in Christiania when the city was founded. The stone tablets in the wing towards Nedre Slottsgate indicate the building is from 1638, and according to the city antiquary in Oslo, this is Oslo’s oldest known building. There are traces of an even older building on the plot. The date 1640 on it is likely from an extension.

Bankplassen

The square comes from Norges Bank, which was built here in 1828. It is now used by the Museum of Architecture. You pass it on your right as you head into Bankplassen.

The square was renovated in 2016 for Norge Banks 200th anniversary. The square got new light poles using historic luminaires.

The Christiania Theatre was located on Bankplassen from 1837 to 1899. Cafe Engelbret quickly became a permanent place for many artists. The theatre was torn down to make way for Norges Bank, whose new building opened in 1900.

You can see Cafe Engelbret at the other end of the square.

Cafe Engebret

The restaurant is named after the founder Engebret Christoffersen, who started the restaurant in 1857. It moved here in 1863 and has undergone very few changes. The building is from 1760.

The Engebret Movement, a network of female journalists in Oslo, took their name from the place. They existed for 10 years and the goal was to promote female journalists in the business. The network worked for gender equality through the Norwegian Journalists Association. They wanted equal pay and better working conditions.

Café Engebret was popular for many artists because the old Christiania Theatre was located here from 1837 to 1899. Engebret became a permanent place for many artists. The theatre was torn down to make way for the second Norges bank building, which opened in 1900.

Kongens gate

This is one of the original streets of Christiania, laid out in 1624. If you turn right instead of left, you’ll see the road leads to the fortress. Most of the part we are walking through has been rebuilt over the years, with the buildings here from 1638.

Kongens gate 6 is from 1915. It is considered Norway’s first modern business building.

Tollbugata 19

Head into Tollbugata to look at building number 19.

This building is a small apartment building from 1687, though it has some parts on it that are older. The irons on the side of the building are beautifully decorated.

Prinsens gate 18

You’ve now made it to the north of Kvadraturen. On your right is a white building – this is Prinsens gate 18. It is the oldest house on Prinsens gate. It is from 1640 and was originally one floor but was later extended to two floors. Andreas Tofte, who was Oslo’s first mayor (1837-38), lived and ran a business here from 1824 to 1848.

In 1989, the property was severely damaged after a pyromaniac lit the building. The owner chose to restore the building, but it was upgraded to today’s standards. During the work, ceiling decorations from the 17th century were uncovered and restored

Prinsens gate

Prinsens gate is a 600m long street that runs through Kvadraturen. The street is mostly modern office buildings. Most were replaced after a large fire in 1858 destroyed 40 buildings. The buildings were rebuilt with businesses in mind, mostly because by this point fewer people were living in Kvadraturen. Historically, there were several pubs here and the street was very well known for its social activities. Halvorsen’s patisserie on Wessels plass has been running in the same place since 1881.

Kirkegata

The street, which means “Church Street”, runs from Bankplassen to Stortorvet, where Oslo Cathedral is today. It was originally called Prindsens gang and got its current name when Oslo Cathedral was completed. Originally this was a street for the rich, but after the fire of 1858 many properties were rebuilt for businesses. In the 19th century, this was the city’s main thoroughfare.

Rådhusgata 11 / Statholdergården

You’ve now made it to the north of Kvadraturen. On your right is a white building – this is Prinsens gate 18. It is the oldest house on Prinsens gate. It is from 1640 and was originally one floor but was later extended to two floors. Andreas Tofte, who was Oslo’s first mayor (1837-38), lived and ran a business here from 1824 to 1848.

In 1989, the property was severely damaged after a pyromaniac lit the building. The owner chose to restore the building, but it was upgraded to today’s standards. During the work, ceiling decorations from the 17th century were uncovered and restored.

Rådhusgata 10, 12, 14

This building was originally three small properties that were constructed at the end of the 1620s. They have all undergone changes through the years – they were last restored in 1980 and incorporated into Norges Bank.

Grev Wedels Plass

This is a lovely park that was laid out in 1869. The name comes from Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg (1779-1840), who was the president of the Storting (parliament), an ironworks owner, county governor, and finance minister.

After Akershus was closed as an active fortress in 1818, the area was turned into a government quarter. The Parliament and the Supreme Court were initially going to stand here, but it was banned by military authorities in 1836. The Park opened instead in the 1860s and quickly developed a bad reputation for hosting illegal activities. In the 1930s, it was paved over and turned into a car park. During World War II, the square was used for barracks and shelters. In 1988, the park was reconstructed and reopened.

The red building to your left is from 1840. The white building across the street and to the right is the Army Depot, a warehouse building designed in Empire Style from 1828. Further down is an orange building – this is Ridehuset. It was originally a stable but opened in 2007 as a concert venue. There’s an entrance to Akershus Fortress by Ridehuset.

Gamle Logen

The building on the opposite end is Gamle Logen. It was built in 1839 as a Masonic Lodge and banquet hall. Several events have been held in this building, such as a special dinner for Fridtjof Nansen and his crew after their first Fram trip. Until World War II, it was also a popular concert venue. Edvard Grieg (there’s a bust of him outside), Ole Bull, Johan Svensen and Halfdan Kierulf have performed here. After World War II, the building was used as the Court of Appeal, and this is where Vidkun Quisling was sentenced to death on the 10th of September 1945. It was also used as a canteen by Oslo’s dock workers. After extensive rehabilitation, it reopened in 1988 as a concert and cultural venue.

Military Hospital

Now you can see the Military Hospital. It is a beautiful wooden building from 1807 and was originally built as a hospital for soldiers. As Denmark-Norway was heading into the Napoleonic Wars, a new hospital was needed. After Norway became Swedish in 1814, it was a general hospital for the public, which it remained until 1883. It was then dismantled and taken to the Norwegian Folk Museum, where it sat in storage until 1983. Now it’s back at its original spot.

Garmanngården

At the corner of Rådhusgata and Dronningens gate is a beautiful red home. It is Garmanngarden, one of the city’s oldest standing buildings. Parts of the building are from 1622 (before Oslo burned in 1624), though most of the building is from 1625-1630. The anchors on the building have the date 1647, which is probably when the building got its current appearance. For its first 100 hours, the building was the residence of important men in Oslo, such as Land Commissioner Johan Garmann (where the property got its name from) and Governor Just Høeg.

The building was given to the city by King Chrisitan VI as the new town hall in 1734. It was also used as a courtroom, a meeting room for the magistrate, a theatre, concert and party room. There was also a police station, detention facilities and a prison.

Today the building is used by the Society for Oslo Byes Vel, which is a historical association that promotes the city’s history. All those blue signs on old buildings are managed by Oslo Byes Vel.

The War School

This building was established in 1804 to train officers for the Norwegian army. The students received a five-year education. Most of the cadets were listed, and the majority were the sons of officers. The school provided insight into military technology, general education, physical education, and military education. This is one of the world’s oldest military academies that has been in continuous education.

Posthallen

Across the street is ‘Posthallen’. It was built between 1914 and 1924 as Oslo’s main post office. Today the building is used as shops and apartments – the post office moved to a different building in 2004.

Pascal Patisserie

Diagonally across from the Military School is Pascal Patisserie, a very famous place for sweet treats. There has been a patisserie here since 1650. Sadly, the original building burned down and wasn’t rebuilt until 1870. The interior is left fully untouched from 1895.

The current owner is the ninth owner of the patisserie. It is Pascal Dupuy, a French pastry chef who came to Norway in the 1980s and opened his patisserie in this building in 1995. Pascal Dupuy has gained international recognition for his products, and he is considered one of the world’s best confectioners. He even has a show on Norwegian television that follows him educating his staff and creating unique pieces for special events.

There are multiple Pascal patisseries around Oslo, but this one is the one to visit. They serve French-inspired lunch dishes plus many good desserts. You can also admire the original interior, the glass roof, and a fresco painted by Åsmund Stray in 1895.

Treschowgården

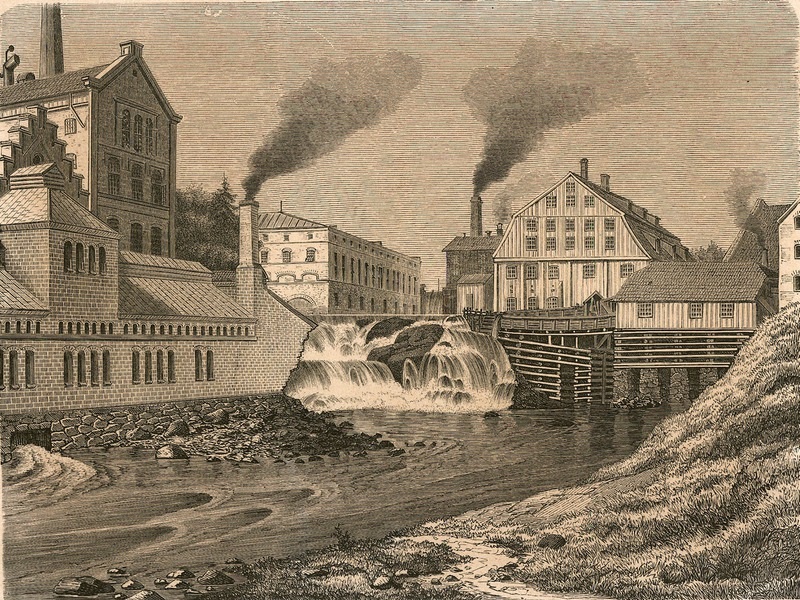

This building was built for Gerhard Treschow, an immigrant from Denmark who became the customs officer in 1683. He ended up becoming one of the city’s largest factory owners with sawmills, brickworks, a paper mill, oil mill, and soap factory. He bought the property in 1710. For a while, it was the Cathedral School, and then it was a hotel. Today it is an office building for the Fred Olsen shipping company.

Oslo Stock Exchange

This building was built for Gerhard Treschow, an immigrant from Denmark who became the customs officer in 1683. He ended up becoming one of the city’s largest factory owners with sawmills, brickworks, a paper mill, oil mill, and soap factory. He bought the property in 1710. For a while, it was the Cathedral School, and then it was a hotel. Today it is an office building for the Fred Olsen shipping company.

Customs Office

This is the customs house. There have been five customs houses on this site – the first one was built by Gerhard Treschow in the 1680s, but it was replaced by the next customs officer, Frantz Jørgensen. He wanted his own customs house, so had it designed to his taste. The site used to be on the pier, but it was filled in 1957-1960.

Frantz’s customs house was so rotten by 1770 that it was torn down and replaced. However, in 1785 a huge fire destroyed the pier area, customs house included. In 1790 mason and architect Hans Christian Lind built a new customs house, now number 4. It was torn down and replaced in 1895. That building is the one we see today.

Customs Warehouse

This is a customs warehouse from 1915. Behind is the Tollpakkhuset, a customs warehouse from 1915. It now houses the Norwegian Customs Museum. The museum has all the uniforms spanning 350 years, plus all the stuff people tried to smuggle into Norway – this alone makes for a very entertaining visit.

Customs Office

You’ve now reached the library/Oslo Opera House area, with the Central Station on your left. I hope you enjoyed this walk around Christiania!

Enjoy More of Oslo

Visit the travel guide page to see road-trips, restaurants, and top activities that you can do.