From the First People to Klippfisk: the History of Kristiansund

- 0 comments

- by Emma

From the First People to Klippfisk: the History of Kristiansund

Kristiansund is an important place in Norway. Today it’s associated with the klippfisk (clip fish, dried and salted cod) trade that took place here. And rightly so! Thanks to klippfisk, we have Kristiansund. Still, there’s a lot more to this island city that is worth knowing before you make the trip there. The history of Kristiansund is truly fascinating.

Here’s my historical overview of Kristiansund. As always, I have relied on books and websites that provide an incredible amount of detail. You can find links to them throughout and at the bottom of this article.

In this article...

Kristiansund is the oldest settlement in Norway

Kristiansund wasn’t always known as Kristiansund. The name came in 1742 when King Christian VI gave the settlement a town charter. The town gets its name from him, but more on that later.

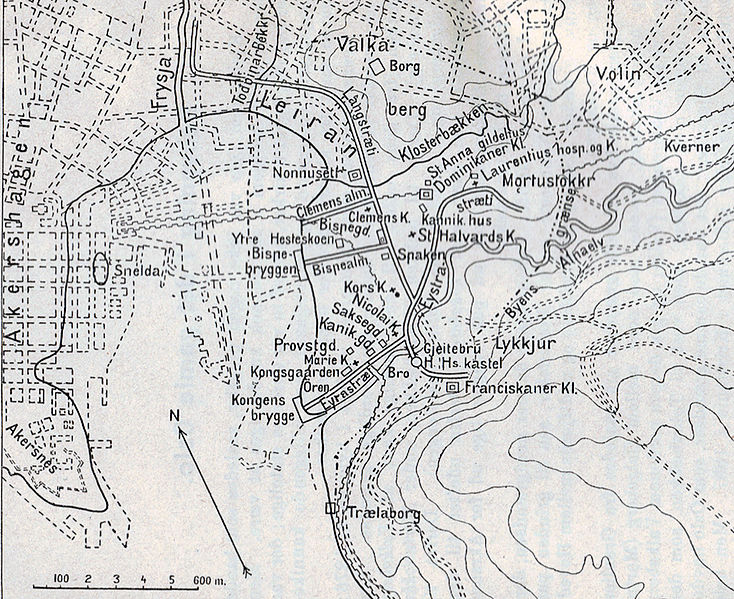

The first name of Kristiansund is Fosna. It’s generally believed that this place was one of the earliest settlements after the last Ice Age. People likely arrived around 8000BC as Kristiansund (and its surrounds) were one of the first ice-free places in Norway. Additionally, the surrounding sea had lots of food. Additionally, there was lots of stone and flint they could use as weapons and tools.

Today, the first Norwegian peoples as known as the ‘Fosna culture’. Traces of these peoples were first made in Voldvatnet (Vold Lake) in 1909. Kristiansund isn’t the only place where the Fosna people lived – it’s just where they got their name. Fosna is an umbrella term for the oldest settlements along the Norwegian coast. Additionally, similar cultures were on the coastline in Sweden and Northern Germany. The sea used to be much higher – today their settlements are 60-70m above present sea level.

You can visit Voldvatnet (also spelt Vollvatnet) today. Sadly it’s in a very crowded industrial place in Kristiansund.

Wiki (English) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fosna%E2%80%93Hensbacka_culture

Wiki (Norwegian) https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fosna-Hensbacka-kulturen

Vikings around Kristiansund

While Kristiansund itself is not mentioned in the Viking Age, we know the Vikings were in this area. Firstly, because nearby Tingvoll was a historic meeting place. ‘Ting’ is an Old Norse word that means ‘assembly’. It’s where the chieftains would meet to discuss important matters. Secondly, the nearby island of Frei is mentioned in connection to a battle that took place during the Viking Age. You can read about it on my page about driving from Oppdal to Kristiansund as we drive past the place where it happened.

Trade & Stockfish on the island of Grip

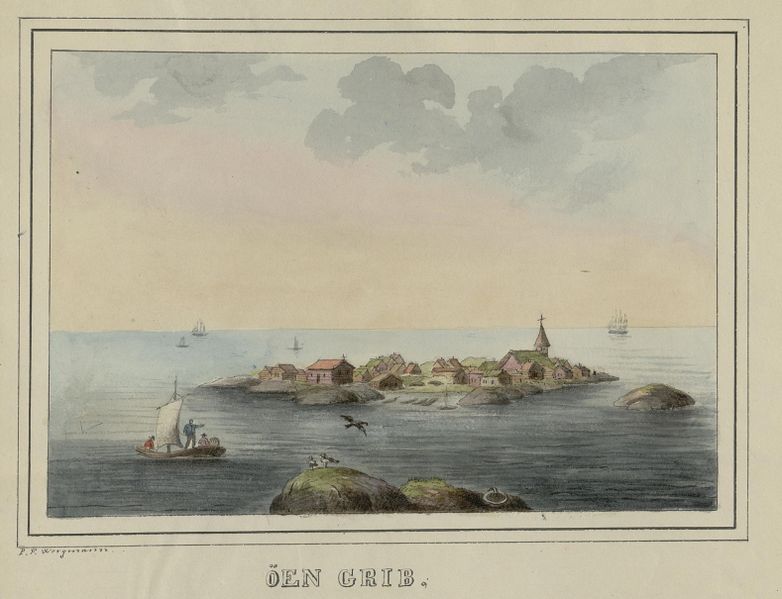

Grip is one of the places I hope to visit and write about someday, but if you go to Kristiansund it’s an island you can take a day trip to. I recommend it.

We know Kristiansund wasn’t very populated in the early years, but the island of Grip sure was. The first settlement of Grip is unknown. The island emerged from the sea sometime between 3500BC and 2500BC. This is well after the Fosna people of Kristiansund (and surrounds). There are no archaeological traces on the island, which is notoriously hostile. The very first fishermen to settle here must’ve been very brave!

There are no written documents about when Grip was first settled. However, it was likely between the 9th and the 13th centuries. The island has no arable land and no shelter from strong winds, but it does have very rich fisheries. The people who moved here wanted to be close to the fishing grounds. In the 13th century, the Hanseatic League was gaining prominence in Bergen. The export of stockfish from Lofoten was becoming big business. The fishermen likely saw an opportunity in settling on this island, which is on the journey south from Lofoten to Bergen.

Grip became a very important place. In fact, it was the largest settlement in Nordmøre. The island came under the control of the archbishop of Norway, which is common. The church was the wealthiest landowner until the Reformation.

Grip has one of Norway’s 28 remaining stave churches. Grip Stave Church is from 1470 and is the oldest building on the island today. The altarpiece represents the strong connection to the Hanseatic merchants from Europe. Having a decorated stave church on such a remote island indicates how important this island was for the merchants.

The 15th and 16th centuries were the peak period for the island, thanks to the Hanseatic trade. Many wealthy merchants settled on Grip, and the population was as much as 300, making it the largest village in the region. The Hanseatic merchants exported stockfish to Europe, and Grip was one of the production sites.

Everything came crashing down at the Reformation when in 1537 King Christian III seized all church property in Norway. From the 18th century onwards, several harsh storms hit Grip, and the fishing grounds began to fluctuate. The population came and went depending on how good fishing was. No one lives permanently on the island today. Simply put, the island didn’t have a good enough location to develop a city. Additionally, towns by the fjords were becoming more popular as timber export grew. The houses today are holiday homes. You can visit Grip via a ferry from Kristiansund.

A harbour founded amongst islands

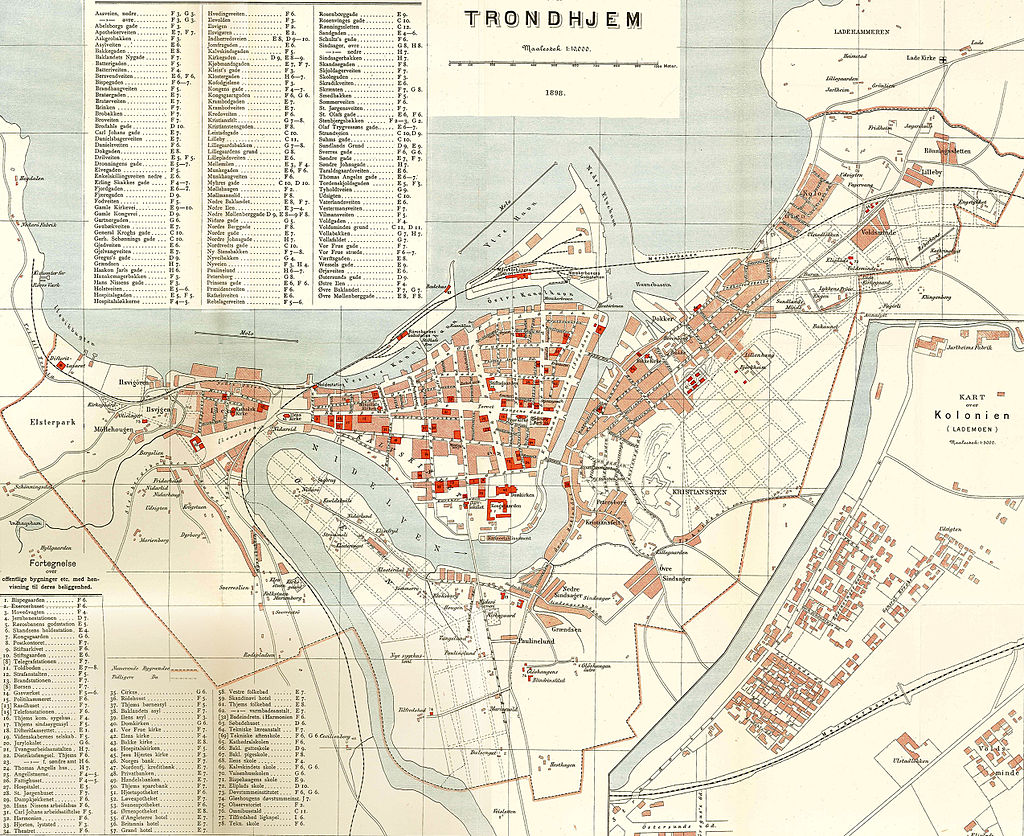

Grip was where the action was, but there was a tiny settlement in Kristiansund. At the time it was known as Lille-Fosen based on the first peoples who lived here. The people lived on the meadow by the bay, Vågen, and this is where the city began to grow. You can see it on a map. Firstly, it’s where the Shipbuilding Museum is. Secondly, you can see how the bay is sheltered from strong winds coming in from the North Sea.

We know Grip wasn’t a great place to live. So, as trade moved away towards timber in the 17th century, merchants started looking for a natural harbour. This is the basis for commercial expansion and settlement in many places along the Norwegian coast. This is how Kristiansund began to grow. Even though Grip was important for boat traffic sailing along the coast, the significance of Lille-Fosen’s harbour between three islands increased. The small community grew from the 17th century, especially when the Dutch discovered it.

The Golden Age of the Dutch Merchants, otherwise known as Hollendertiden

The Dutch began coming to Norway in the 16th and 17th century to take all the timber. At the time, the Netherlands was the leading shipbuilding nation in Europe. To maintain this they needed a lot of timber. But not any timber. They needed long, straight trees with strong resilience to withstand harsh weather. Norway had large quantities of timber that they could buy at a reasonable price.

Fun fact: Amsterdam is literally built on Norwegian timber as timber was needed for foundations under large buildings.

The Dutch came to the area around Kristiansund. There are some rich forests on the fjords, and the harbour of Kristiansund (then Lille-Fosen) was safe and suitable for them. The harbour Vågen became a permanent mooring and gathering place for vessels that visited the district. A customs station was established in 1630 to control the timber trade.

The Dutch didn’t only come to take all the timber; they brought goods for sale. Ceramics were very important. It’s likely they also brought wine, beer and liquors to Kristiansund. The Norwegians profited heavily from this, especially the forest and sawmill owners. They didn’t only go to Kristiansund; many coastal towns in Sørlandet, Østlandet, Vestlandet and Nordmøre (the stretch of coast from Kristiansand to Kristiansund) saw Dutch merchants come here.

The Dutch period lasted until 1850.

In the 1690s, something happened that would change Kristiansund forever. A Dutchman named Jappe Ippes brought knowledge about the production of klippfisk. He received a royal privilege that gave him permission to manufacture and export klippfisk. And so, a new industry was born.

The city founded on Klippfisk

Kristiansund is said to be founded on klippfisk. After Jappe Ippes introduced the process in the 1690s, men came to Kristiansund to learn and expand the business. One of the most prominent men to come here was the Scotsman John Ramsay. John turned it into a large company, and soon after the most enterprising of merchants in Kristiansund gained control of all stages of klippfisk production. They received the catch, processed it, and then exported it.

We should back up a moment. What is klippfisk? It was virtually unknown in Norwegian cuisine at the time. Clipfish (I’m using the Norwegian name, klippfisk) is cod that has been both salted and dried. It is a descendant of stockfish – cod that dries unsalted and is as old as the Viking times. The process of salting fish started in the 15th century but was introduced to Norway by the Dutch.

‘Klippfisk’ means ‘rock fish’ because they leave the fish out on rocks to dry.

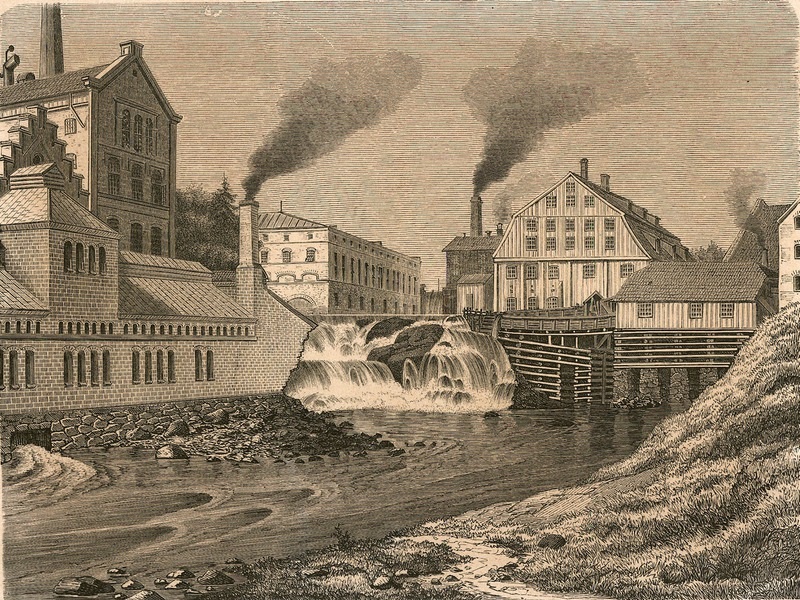

There’s a big overview of how they make klippfisk (in English) here: https://cod.fromnorway.com/norwegian-cod/clipfish/

During the 18th century, klippfisk became a major industry. Boats came in from the sea with the salted catch. Producing klippfisk was labour intensive, and soon factories popped up all over Vågen. They wash the fish before salting it again and drying it on a ‘fish mountain’. They then press it flat for two weeks to allow the saltwater to drain. Milnbrygga and Milnbergan are important cultural monuments from this time. Today, the whole process is modern and explained in that link above.

Thanks to klippfisk, the town began to expand. Lille-Fosen built up a large fleet with shipyards and ropeways. Expertise in shipbuilding was obtained from Copenhagen. The city grew in the 18th century as klippfisk became the major industry.

Lille-Fosen becomes Kristiansund

The town got its name after King Christian VI granted it a town charter in 1742. He named it after himself, much like the Danish kings before him had named towns after themselves (see Kristiania/Oslo and Kristiansand in the south). Yes, there is often some confusion between Kristiansund and Kristiansand. Before postcodes, it was obligatory to add an N (for north) to Kristiansund and an S (for south) for Kristiansand. Some people still practice this, and when I say I’m going to Kristiansund, I have to word it like “KristianSUND (the one in the north)”.

The town charter meant expansion. Commerce in the town developed during the following decades and Kristiansund prospered. The demand for klippfisk was so great that the fishermen could not supply it all. Fishermen brought cod down from Lofoten and Finnmark to make the klippfisk. From the 1820s, salted herring also became an important export product. The city got a large fleet of sailing vessels, yachts, and galleys for traffic. The market expanded to the United States. The Danish merchant Christian Johnsen learned the principles of klippfisk trade in Bilbao and established his business in Kristiansund that exported klippfisk to Asia, South America, and Europe. Another klippfisk merchant, Nicolai H. Knudtzon, was Norway’s richest man at the end of the 19th century.

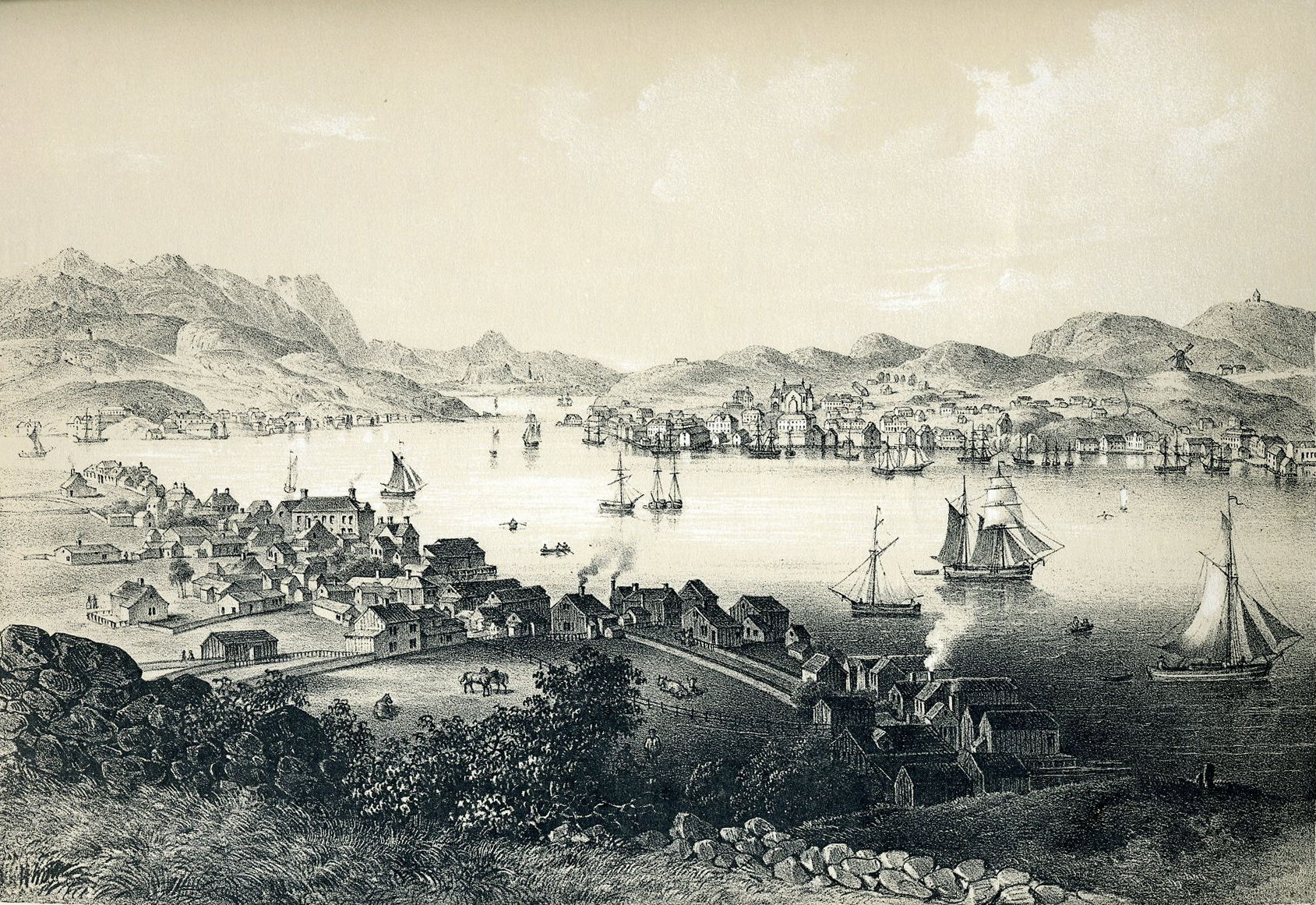

By the end of the 19th century, Kristiansund was a wealthy and prosperous town with merchant mansions, quaysides and wharves.

The Spanish Era & Eventual Collapse

Around the time the Dutch trade was ending, the Spanish began to come to Kristiansund. Spain is one of the countries that ate a lot of klippfisk, due to the rules around Catholicism and not eating meat. Additionally, the Spanish had introduced bacalao using klippfisk.

Basically, the Spanish came to Kristiansund to buy klippfisk without a middle man. The Spanish sailors introduced bacalao to the city.

Fun fact: The ships that brought klippfisk to Spain brought back soil as ballast. The area around Kristiansund had little soil and Spanish soil was used in, among other things, the towns first public cemetery.

The klippfisk business continued until 1884. A sudden fall in market prices in Spain hit the companies in Kristiansund. All klippfisk exporters, with one exception, went bankrupt.

1870: https://digitaltmuseum.no/011013318326/kristiansund-more-og-romsdal-lunds-nr-21

Kristiansund or Fosna?

When Norway became independent in 1905, many cities started discussing the possibility of changing their name back. The Danes had changed many Norwegian town names. This is most prominent in Oslo, which was named Kristiania by Christian IV and changed back shortly after World War I. In Kristiansund, it was argued that the old name Fosna should replace Kristiansund. In 1929, a vote showed overwhelmingly that 99.1% of locals didn’t want the name changed.

The 1920s & 1930s: Wealth and Collapse

At the end of the 19th century, Kristiansund was a beautiful city with many large merchant farms, boathouses and piers. The city didn’t have much of a zoning plan; instead, a house went wherever you could fit it. While this was impractical when cars were introduced, it was charming. Most of the houses were wooden.

Kristiansund in 1882: https://digitaltmuseum.no/011013318183/gatebilde-fra-torvet-kirkelandet-kristianssund-1882-i-forgrunnen-til-venstre

In 1928, 32 years before a national opera was founded in Oslo, the Norwegian Peoples Opera was founded in Kristiansund. So, opera came to Norway through Kristiansund. Today there is an opera festival that takes place every February.

Due to the limited scope of commercial activities, Kristiansund struggled to recover after the post-WWI economic collapse. Attempts in the 1930s to find new industries for Kristiansund began, but that was all halted by World War II.

World War II

At the end of April 1940, when Nazi Germany was invading Norway, Kristiansund was subject to almost four days of continuous bombing by the German Luftwaffe. The town was left almost in ruins. Five people died, and 800 buildings were destroyed by fires that ravaged for days after the bombing. This corresponds to 28% of Norway’s total war damage to buildings during World War II.

Why did Germany bomb Kristiansund? Well, they thought the Norwegian King and the government were hiding here. They were not; they were in Molde.

Little could be rebuilt during the war, and most of the inhabitants who became homeless had to live in barracks until the end of the war. Some Swedish prefabricated houses were built in Kristiansund, and they still stand today. The street they are on is Vuggaveien.

Post-war Rebuilding

After the war, Norwegian architects got to re-designing towns that were damaged during the war. The rebuilding was initiated under the ‘Brente steders regulation’ (Burnt Places Regulation). While a zoning plan was ready as early as August 1940, work couldn’t begin until after the war.

Kristiansund got typical post-war architecture that characterises many of these ‘burnt places’. It’s best described as a sober functional style. The central parts of the city completely changed from charming, wooden districts to planned streets with concrete blocks. The building of Kirkelandet Church in 1964 marked the end of re-building.

By 1950, 68% of the city had been rebuilt.

Today, the reconstruction of Kristiansund is highlighted as one of the 20th century’s most worthy cultural environments in Norway. Furthermore, the town has the best-preserved examples of post-war architecture. The area that was rebuilt is the ‘Reconstruction City’ and has a very strong concentration of post-war houses not found elsewhere in Norway.

The main street, Kaibakken, is a great example of post-war design. It was a key element in the city’s reconstruction architecture. Many ‘burnt places’ in Norway got long, main streets like this one. They found inspiration in streets like the Champs Eylyss in Paris.

Finding new industries

After the war, Kristiansund knew it had to expand beyond klippfisk. While klippfisk is still at the heart of the city, there are new industries in Kristiansund. The food industry is still important, but Kristiansund is now a central operations and supply base for the offshore oil industry. Oil is now the main commercial basis in the town.

Modern Kristiansund's Highlights

Today 24,334 people live in Kristiansund and it has all the facilities you’d ever need. The population of Kristiansund is actually rising.

Transport connections to Kristiansund are pretty good. Besides ferries out to the surrounding area, Kristiansund has the Norwegian National Road 70 and the European route E39. The airport, Kvernberget, has connections to major cities in Norway plus some European destinations in the summer. Kristiansund is also a port on the Hurtigruten. If you take the Hurtigruten southbound (Kirkenes – Bergen), you stop in Kristiansund for one hour in the afternoon. They have excursions to the Atlantic Road.

There are plenty of primary, middle and upper secondary schools in Kristiansund. However, there no higher education facilities.

Culture & Tradition

Kristiansund has a rich cultural life with the Opera Festival, the Nordic Light International Festival of Photography, the City Festival and the Tahiti Festival. The Opera House is the oldest in Norway. It is from 1914 and is one of the few buildings to survive the World War II bombing. Another one of the few buildings to survive World War II is Nordlandet Church, which is built of stone from 1914. It dominates the skyline on the island of Nordlandet. The newest church is Kirkelandet Church, which was the final postwar building in Kristiansund.

As you may imagine, there’s also a rich food culture in Kristiansund. Besides bacalao, another main dish is blandaball. I know the name doesn’t sound great in English. It’s a fishball consisting of fish (of course!), onion and potato. The ingredients are ground and shaped. In the middle is a piece of pork, just like a Norwegian Kinder Surprise. They don’t look great, but they taste excellent.

There are plenty of museums in Kristiansund about the history of the city. The Norwegian Bacalao Museum is the most popular. The Nordmøre Museum is also located here, plus the historic Mellemvaerftet Shipyard that you can visit. Vågen – the old harbour – has many interesting cultural monuments and is a great place to visit. Some old merchant farms and wharves are still standing. The old town was somehow spared during the bombing and it gives an insight into what Kristiansund used to look like.

Lastly, the big thing people come here to see is the famous Atlantic Road – one of 18 national tourist roads in Norway. But more on that in a separate article.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this overview of Kristiansund’s history, and that it’s inspired you to visit someday!