The Fascinating History of Mining in Røros

I love Røros. It is one of those places that has been on my list for a while, and finally in September 2020 I got to visit. I’m in love. If I didn’t live in Bergen, this website would be called iloveroros.net.

One of the big reasons I love Røros is the history. There is so much here. Røros is a UNESCO World Heritage Area for its preserved town centre and unique mining heritage. There’s a lot to unpack, so I’ve put it all together into one article.

This is a summarised version of the history of mining in Røros. There is a wealth of information online, and I’ve done my best to create a list of resources for you. Additionally, the museum shop is full of books about mining. I’m very grateful for these resources, as it allows me to write my version of the mining history. I couldn’t have done it without the readily available material online. I’ve posted all the links at the bottom of this page.

In this article...

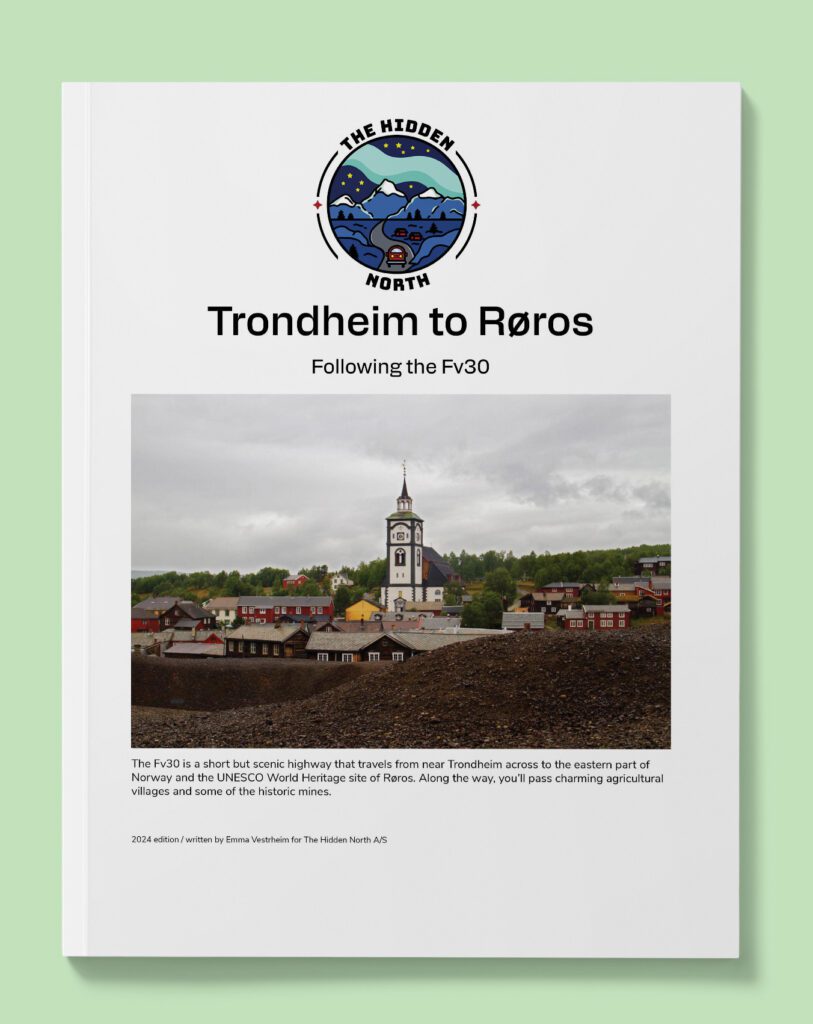

The Fv30 Highway

You can reach Røros by taking the Fv30 from near Trondheim. You can find my guide to the Fv30 by clicking the link below.

The Early Years

There wasn’t much here before mining came. A South Sami community grazed their reindeer here, and there were a few scattered settlements. That’s about it.

Interest in mining started with the Danish-Norwegian King, Christian IV. Due to all the wars with Sweden, Denmark-Norway was in desperate need of minerals, metal deposits, and money. The three m’s. There was another mine already here: Kvikne Copper Works. It was – at the time – the country’s largest mine. Assuming there were more mining opportunities, Christian IV put out a statement. In it, he said that great rewards will come to those who found some of that good stuff under the ground.

A local man discovered copper in the ground while out reindeer hunting. After that, it took just months before the first mine – Old Storwartz – was in operation. Men came from Kvikne to help build up the mine. Operations began in August 1644 after recruiting some Norwegian soldiers, but it wasn’t great. There were bad deposits here, and the mine was only in operation for a few months. Eventually, though, the region became a good sport for mining and new mines went up all over the landscape.

The establishment of Røros Kobberverk (Røros Copper Works) was to manage all mining activity. The company operated from 1644 until its closure in 1977.

The Circumference

Once it was clear that mining was the future of the region, Christian IV issued a letter of privilege to Røros Kobberverk. The letter gave them exclusive rights to minerals, forests and watercourses within an area bounded by a circle. The circle has a radius of four ancient Norwegian miles (45.2km) with a centre at the Old Storwaltz mine. This is the Circumference.

What happened if you were one of the few farmers in that area? Well, for a fee, the farmers had to sell their products and goods to Røros Kobberverk and do work for them. But this wasn’t a bad thing; back then the farmers needed a second source of income, and the mining activity was able to provide that. The farmers who did work for the plant typically transported goods or provided timber. The farmers had one day off a week and one month off a year, which they used for their farms.

Within the Circumference, Røros began to grow as a hub for the mining activity. it also helped that the main smelting plant, now a museum, was here.

Today the UNESCO World Heritage Area is the Circumference. When driving in and out of Røros, you will see signs indicating where the UNESCO site begins. That’s the Circumference! How many times have I said Circumference in this piece?

Bergstad or Røros

Sometimes you will see Røros mentioned as ‘Bergstad’. A Bergstad is a community that is centred around mining. These mining towns had their own laws and royal agreements. The mining town was in many ways a state, responsible for everything. In Norway, there were only ever two mining towns: Kongsberg and Røros. Today Kongsberg has city status, but Røros is still a designated ‘Bergstad’. It’s more unique that way.

How did Røros Kobberverk Work?

This one is a little tricky. The company was a partnership with many owners, and copper was split among the owners according to the size of their share in the company. They then had to sell the copper on their own.

I’ll explain how the workers well, worked, further down.

Røros Kobberverk was responsible for the food supplies, education and health services within the Circumference and the surrounding area.

The Røros website has a detailed overview of the company structure, which you can view here.

Early Mining

The most common minerals extracted were copper, zinc, chrome and pyrites. Copper was the dominant mineral, though.

Early mining was very, very difficult. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, most work was by hand. They broke ore out of the rock by lighting enormous wood fires. The fire heats the rock and forces it to become brittle and crack. Crowbars got the ore out of the rock.

They needed a lot of wood to do this. When there was a lack of timber, they used explosives. They drilled holes by hand, using sledgehammers, chisels and crowbars. Gunpowder went in the holes, and then they sealed the holes with clay or wooden plugs. After this, they lit the fuse. This way was easier, but having to make holes in the rock was incredibly labour intensive.

There were many constant issues during the early years of mining. Air ventilation was a problem, as was pumping out water and transporting the ore. Carbon and sulphur gases from the fires and explosives had to leave the mines as quickly as possible. The shafts ensured some circulation of air, and the shafts also lifted out the ore and pumped water. In the early years, individuals had to carry the water out with buckets. As technology developed, though, there were horse-driven bucketing plus water wheels to supply power.

Growth & Peak of Mining

It was a shaky start; mining didn’t really take off until 100 years after the founding of Røros Kobberverk. In a period starting from 1740, several mines were bringing in a large number of goods.

A good sign of the wealth of Røros Kobberverk is the church. It is from 1784 and funded by the company. It made a statement of the Company’s wealth and authority. It’s also fun to know: No other Norwegian company ever contributed so much to the royal income as Røros.

Røros’ heyday lasted from 1740 until 1814 when Norway’s union with Denmark ended. The mines continued to be profitable until the 1860s when copper prices fell and operations became more expensive.

Røros Grows as a Town

The first Smeltehytta (now the museum) was built on the river that flows through today’s Røros in 1646. A clear town plan is seen on the first map of Røros from 1658. The map shows two main streets running parallel joined by linking, smaller lanes. The town today has this same layout. The climate played a huge part in the development of Røros. There was much more shelter by putting the houses close together and protecting against the winter frosts and bad weather. Most of the houses are around a central, sheltered courtyard.

Røros was burned down by Swedish troops in 1678 and 1679, and the town we see today is from after these fires.

Much of the layout of the town is based on status. On the eastern side of Storgata is where you’ll find the company executive’s homes. At the bottom of the street is the impressive General Manager’s house in a Baroque style.

On Kjerkgata are the labourer’s houses; built on both sides of an evenly spaced street. At the top is the church.

Haugan is a district that grew in the 17th century. It doesn’t follow the same town plan. The buildings are built more haphazardly. From the middle of the 18th century small single cottages went up – many without outhouses.

Life as a Worker in Røros

The majority of people who worked at Røros Kobberverk usually acquired a small farm or smallholding, and they kept animals on their property. The animals are a source of food, and a family without animals would struggle to live here. Also, by having a farm, the families had another way to make money in case it had been a bad year for mining. This was common until as late as the 1960s.

Anyone living in Røros had to contribute to mining somehow. The women often worked as cleaners in wealthy homes, or they produced food or clothing.

In the early years of mining, the miners worked 10-hour days 5 days a week. There was some flexibility; miners could leave when it suited them provided they work back the hours they had taken free. However, this luxury ended in 1713. After that, miners had to live at the mines in barracks for a whole week from Monday to Friday. The barracks had bunk beds along the walls and a central fire to keep them warm.

Originally, all employed workers received the same daily wage paid out monthly. From 1720 it became more competitive, with types of work auctioned off for the lowest price. These types of auctions and contracts became common by the 1800s to reduce labour costs and improve efficiency.

The Smelting Process at the Smeltehytta (Smelting Cabins)

The Smeltehytta was important to copper production. Here the copper ore underwent a long and laborious smelting process. Smelting is the process of separating the good stuff from the raw ore.

The first Smeltehytta is from 1646. Typically, the Smeltehytta were close to rivers to utilise hydropower. They were in forests as they required large amounts of timber. The two most important factors when building a Smeltehytta was that it was by a river and close to plenty of timber. The river could not freeze in the winter and had to have enough power to drive the bellows that forced air into the smelting furnaces.

The first Smeltehytta is in Røros. Eventually, they were built all over the Circumference and surrounding area. At the peak, there were twelve Smeltehytta’s in the Circumference. It was cheaper to transport the ore to a Smeltehytta than it was to transport timber to Røros. The Røros smelter survived almost the entire length of Røros Kobberverk’s history. Today, it’s a museum – more on that below.

You’ll see slag all over the landscape, most famously in Røros town centre. Slag is the by-product left over after a metal has been separated (i.e. smelted) from its raw ore. The most famous ‘slag heaps’ are by the Smeltehytta in Røros – they make for a great climb and photo-point today!

Transportation & the Winter Road

There was an enormous need for transportation; from the mine to the Smeltehytta and then onwards to the outside world.

They did most of the transportation during winter. It was much easier to transport goods on frozen lakes and snow. The Winter Road was one of the busiest routes between Sweden and Røros. The road began in Falun, a mining town in Sweden, and went over lakes, rivers and marshlands to Røros. The trip was demanding; the towns are 400km apart (with the modern highway) and the journey could take over six weeks. If the weather was good, the sledge could travel up to 40km a day.

The transport was done using horses and sledges, and hundreds of horses could be queuing in Røros or one of the Smeltehytta at any one time. Sledges are much easier to pull in winter.

Because it was such a busy road, many farms and inns were established. They catered to the needs of drivers so both man and horse could find shelter and food. Along the Winter Road is a stretch of farms or inns called Saether, Holla, Korssjøen and Sevatdalen, all typical examples of wayward inns or farms.

Today the journey takes 5.5 hours in a car. The highway mostly follows the old Winter Road.

Modernisation of the Mining Process

From the 1880s, Røros Kobberverk made great investments in modernising the mining process and introducing new technology. By the end of the 1800s, Røros Kobberverks was among the best mines in Europe.

From the mid-19th century, the process of digging out the rock in the mine improved. Dynamite became commonly used from 1870 onwards. Drilling machines came into use at the end of the 19th century. Electricity came to the mines from 1897 onwards.

Improvements were made to the smelting process using the Bessemer method, under Frenchman Mahne’s patent. Before the introduction of this process, the smelting process took many days.

The smelting of copper was eventually centralised at the main plant in Røros and activity at the other Smeltehytta’s discontinued. Sadly the main Smeltehytta at Røros was affected by fires in 1888 and 1953 before burning down in 1975. The building has since been restored.

A new road network was also improved during the 1800s. In 1877, the Røros Railway was completed and became of vital importance for transportation to and from the copper works.

20th Century Decline

The 20th century brought many challenges to Røros Kobberverk. After World War I, work came to a standstill. When it resumed, it was being subsidised by the state. Production continued during World War II, but the smelting plant had stopped until 1946.

Immediately after the war, work was stable. A massive search for minerals was conducted from the air in 1959. The main mine, Olavsgruva, closed in 1972 and efforts were made on deposits at Lergruvbakken where zinc and copper were mined. The cost of zinc and copper was rising, and this was good for the company.

However, in the late 1970s prices dropped and large losses began to hit Røros Kobberverk. In 1977, the Board of Røros Kobberverk found it necessary to submit a notice of bankruptcy. After 333 years of mining activity, Røros Kobberverk ended its operations. At that point, it was Norway’s oldest company.

During its operation, a total of 110,000 tons of copper and 525,000 tons of pyrites was produced.

UNESCO World Heritage

Røros was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1980. In 2010, the listing was expanded to include the Circumference.

Here’s the reasoning:

Røros Mining Town and Circumference is linked to the copper mines, established in the 17th century and exploited for 333 years until 1977. The site comprises the town and its industrial-rural cultural landscapes; Femundshytta, a smelter, and the Winter Transport Route. Røros contained about 2000 wooden one and two-storey houses and a smelting cabin. Many of these buildings have preserved their blackened wooden facades, giving the town a medieval appearance. Surrounded by a buffer zone, coincident with the area of privileges (the Circumference) granted to the mining enterprise by the Danish-Norwegian Crown, the property illustrates the establishment of a lasting culture based on copper mining in a remote region and harsh climate.

“Røros is a unique mining town built exclusively of wood. The town has for 333 years been a melting pot of cultures and influences from Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Trondheim and the surrounding district. This has resulted in a wooden house environment, which represents much of Norway’s finest traditions, and is unique in our country’s industrial, social, cultural and architectural areas. The mining town of Røros and its surroundings is a characteristic example of a special traditional style of wood architecture creating a unique town 600 metres above sea level.”

The Mines Today: What Can I See?

With all this talk of mining, you must want to visit one by now! Here’s the modern-day practical info for what’s left and what you can see.

Mines to Visit

There is only one mine you can visit the inside of. That’s the Olavsgruva mine; it was in operation from 1936 to 1972. You have to visit with a guided tour.

Click here to visit the Olavsgruva Website.

Around Olavsgruva is a mining area where you can see the remains of other mines. Most need a short walk or hike to get there, though. I’ve marked them on the map. They are explained in detail with images on the Røros website (click here).

Today most mines are filled with water and not accessible to visitors. Some ruins can be seen, and most require a hike to get there.

Here’s my somewhat complete list of the mines you can hike to or easily see. I say ‘somewhat’ because I found information online to be confusing and sometimes contradictory.

The Mines

- Killingdal Mine. This mine was in operation from 1674 to 1986. This was one of the largest in Røros: 2.6 million tonnes of ore were extracted here. It reached a depth of 1,446m – making it one of Northern Europe’s deepest mines. It is filled with water and closed, but the area above ground is partially open. The Killingdal Fjellhotel is partly in the old crew barracks.

- Nordgruvefeltet. This was a mining area where up to a dozen mines used to be. They are in ruins today (see this photo of one of the mines). I’ve marked the area on the map. Click here to view a Wiki page about the area (in Norwegian). This is the area where you’ll find Kongens Gruve, the most ‘in-tact’ mine in the area. You can see the walls of the old larger building and the foundations of the hoisting system. It’s marked on the map. The area does have road access, but the remains are only accessible by hiking. Click here to view images of the mining area. The Roros website has a map of the ruins. They are all in the mountains, so you have to hike here. Click here to view the map.

Surviving Smeltehytta

Sadly, most are in ruins today. The Røros website has a list and map of the Smeltehytta, but only in Norwegian. Here’s a mostly complete list of the Smeltehytta’s you can see in English. I say mostly complete because information online is tricky when it comes to the question: Can I go here today?

- Eidet Smelter. This Smetehytta operated from 1834 to 1887. It was demolished in 1891 and only parts of the furnace are standing. The furnace is the best-preserved furnace left, though, so that’s something! It is considered one of the most important technical artefacts in Trøndelag and the only of its kind in Europe. Click here to visit a website about it.

- Drågas Smelter. The remains today are a roadside stop at Hyttefossen in Ålen. You can park right at the site, but most of the remains some kind of hike. Eidet Smelter is a continuation of Drågas Smelter and in the same area.

- Tolga Smelter. Tolga Smelter is one of the longest lasting Smeltehytta’s, in operation from 1670-1871. Today it’s the Malmplassen Gjestgård – most of the buildings are gone. The whole town of Tolga is a cute little mining town and worth visiting!

- Femund Smelter. This smelter operated from 1743 until 1822, and today you can drive up to it. It is even a place where you can spend the night! Click here to learn about the smelter and click here to learn about spending the night. Here’s some info about a hike in the area.

The best Smeltehytta to visit is the one in Røros. Today it is the main museum for the history of mining and the UNESCO area.

Further Exploration

That’s about it for the history of Røros. I know this was a long article; there’s just so much to talk about.

I’m writing additional articles about Røros – mostly a walking guide and guide to the museum. There’s so much to say about this town.

Have you been to Røros? Let me know in the comments! If you have any additional info or changes you want me to make to this article, please mention them below. This blog grows with your support.

The Fv30 Highway

You can reach Røros by taking the Fv30 from near Trondheim. You can find my guide to the Fv30 by clicking the link below.